Every day, it seems there is another proposal for a new condo in downtown Toronto. The previous councillor’s website itemized development proposals in Ward 13; this city-wide Development Applications map can be filtered by ward.

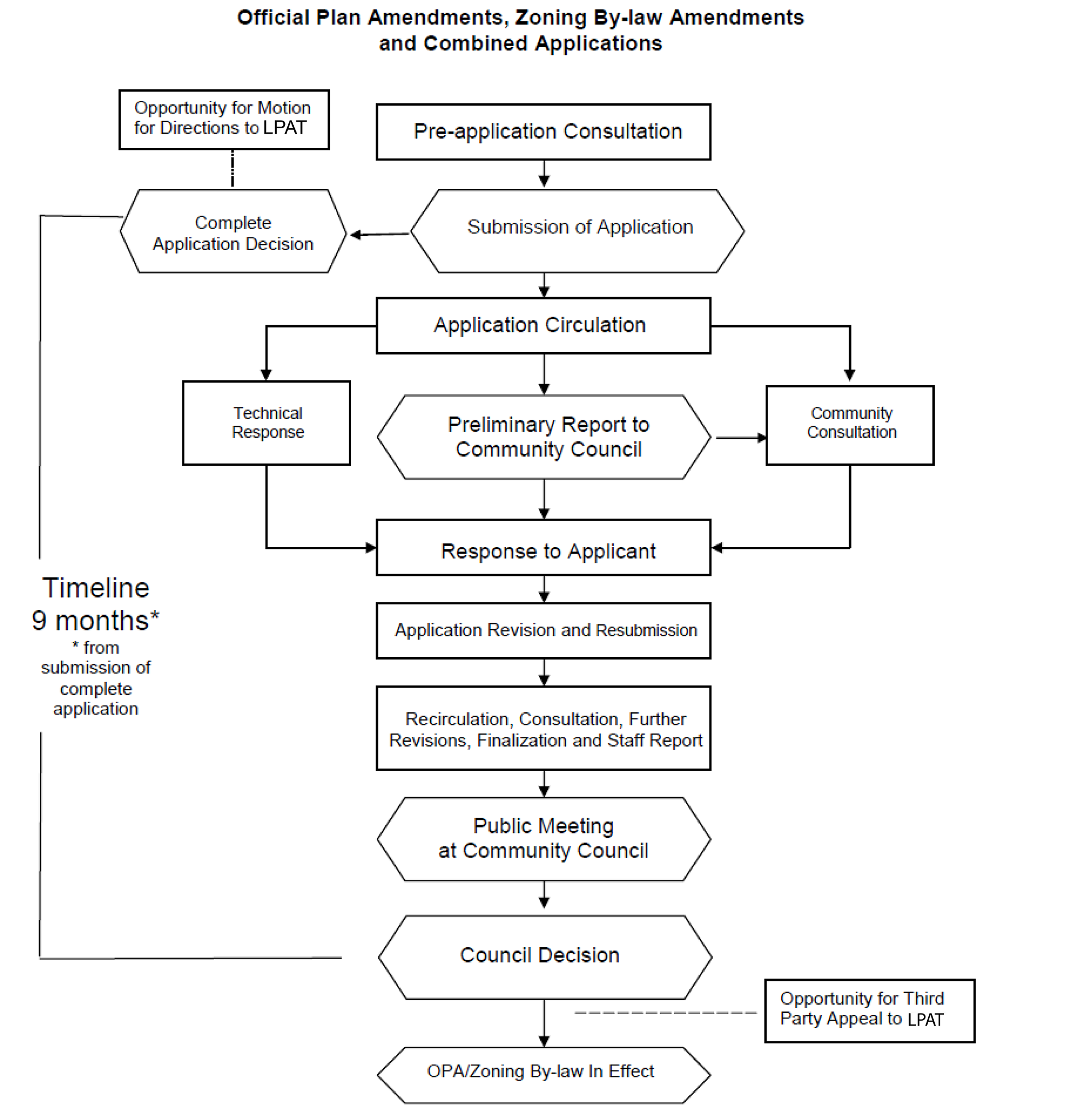

Here is an overview of Toronto’s development approval process (using 471‑479 Queen E as an example). A flowchart (see right) shows the typical sequence of steps; for a detailed description, see the “review process” section on the city’s website. In summary:

- Prior to submitting a formal application, a developer may choose to discuss their proposal with Toronto Planning and the local councillor. (This “pre-application consultation” will become mandatory in Toronto as of Nov 2022. For more details, see here.) New developments often require an Official Plan Amendment (OPA) and/or zoning bylaw amendment. In some areas of the city, the land use guidelines in Toronto’s Official Plan are augmented by more detailed plans, such as the King-Parliament secondary plan.

- Developer submits to the city their formal application, which includes a number of documents, such as the developer’s planning rationale: why they think the proposed building’s height and overall size is justified. Another important document for downtown developments is the Heritage Impact Assessment. At this time, developer may have already publicized the proposed project to the public, on websites such as urbantoronto or blogto.

Note that 90 day after submitted a complete application to the city, the developer can decide to bypass Toronto’s planning process and appeal directly to the province’s OLT (see step 8). - A public notice is posted at the development site, to give the community an overview of the proposed development and a source for more information eg. http://toronto.ca/471QueenStE.

- City planner writes a preliminary report which is submitted to Community Council.

- A public information meeting is held, so the local community can ask questions, and offer verbal comments to the city planner, local councillor and developer. This mandatory public meeting is the only “face-to-face” meeting the developer is obligated to have with local stakeholders. At any time, residents may also voice concerns via phone or email, directly to the planner, city councillor or to Community Council.

- Based on feedback from the city and the public, the developer may revise their plans. Some developers may agree to a series of consultation meetings with a community working group, to try and address specific concerns.

- City planner prepares a final report with recommendations, which is submitted to Community Council and then to City Council, for a decision.

- If the application is refused by the city, or if the city’s review takes more than 90 days, the developer may appeal to Ontario Land Tribunal (OLT), which can override Toronto city planning. Affluent members of the public may also appeal unfavourable development decisions to the OLT. Becoming an active party in an OLT hearing entails an $1,100 fee, hiring expert witnesses (planners, transportation experts etc) as well as legal counsel. Prior to the start of OLT hearings, the city and developer may have confidential negotiations to try and agree on changes which would reduce the proposed development’s negative impacts on the community. Otherwise, the city may retain legal and expert witness to oppose the developer at OLT.

- Once a development has been approved (by City Council or OLT), but before construction starts, the city’s “site plan control” process happens; this will sometimes allows final community input to the developer on details such as exterior cladding, landscaping etc. One example was the Oben Flats development at the corner of Sherbourne and Gerrard.

Notes:

- A revised King-Parliament secondary plan was approved by City Council in 2021, but is “not yet in full force and effect” since has been appealed to the OLT. As a result, so “parts” of the 2017 version remains in force. Other secondary plans include Regent Park and Queen-River.

- 28 Eastern (developer Alterra) is an example of pre-LPAT/OLT negotiations: the Nov 2016 preliminary planning report was “neutral”, a revised April 2018 planning report recommended approval but May 2018 city council disagreed (see TE32.20). Following confidential negotiations, April 2019 City Council recommended approval; this negotiated May 2019 settlement with the developer Alterra was approved by OLT, avoiding a full hearing.

- From the city’s development approval webpage: “Section 37 of the Planning Act authorizes the City, through rezoning, to increase height and/or density beyond what is otherwise permitted in the Zoning By-law in return for facilities, services or matters provided by the owner, referred to as community benefits.” However, payment of Section 37 funds is changing: “Municipal growth-related infrastructure funding tools, such as Section 37 contributions, Section 42 parkland dedication, and a portion of the development charges are proposed to be replaced with a Community Benefits Charge”.

- Another method used by the province to override municipal planning is to issue MZOs (Minister’s Zoning Orders); an MZO was issued for the local Dominion Foundry site.

Further reading:

- explanation from urbantoronto: Official Plans, Zoning, and Amendments

- Ontario using frequent Minister’s Zoning Orders to fast-track development (Toronto Star, Dec 2021)

- Ford government restores OMB rules for development disputes (Toronto Star, May 2019)

- Case study of 2015 St. Lawrence Neighbourhood Heritage Conservation District Plan, which was altered significantly by the July 2020 LPAT ruling that revised or deleted several of the plan’s preservation guidelines, and reduced the HCD boundaries.